The Story and Science of Audio Gates

Making a Scene Presents – The Story and Science of Audio Gates

If you’ve ever been in a recording studio, you know it’s not just about playing music. It’s also about controlling sound. One of the tools that helps engineers shape a clean, powerful recording is something called an audio gate (also known as a noise gate). It’s kind of like a smart door for sound — it opens when you want sound to pass through and closes when you want silence.

How Audio Gates Came to Be

Back in the early days of recording, there were no digital tools, and tape machines picked up everything: the music, the hum from the lights, the hiss from the tape, and even the squeak of the drummer’s stool. Engineers had to find creative ways to make the recording sound clean. If you were recording a live band, you might hear the bass player coughing on the drum mics or the guitarist’s amp humming during a quiet vocal section. By the late 1960s and 70s, companies started designing noise gates — circuits that could automatically cut off unwanted noise when the music stopped or got quiet.

By the late 60s, companies like Kepex and Drawmer started selling standalone noise gates. These boxes let engineers automatically cut out unwanted noise when the signal dropped below a certain level. The technology caught on fast, especially in studios that recorded drums for rock and pop.

They became especially popular in the 1980s during the rise of big, punchy drum sounds in pop and rock. Engineers used gates to make snare drums sound tight and kick drums feel like they hit hard without all the extra ring or bleed from the rest of the kit. It became part of the sound. Producers like Hugh Padgham used gates in creative ways — especially with reverb — to create that famous “Phil Collins” snare sound: huge and punchy, but stopping dead instead of ringing out.

How an Audio Gate Works

Think of a gate as having an invisible guard who only lets sound through if it’s loud enough. You set a threshold, which is the volume level that triggers the gate to open. If the sound is below that level (like hum or background chatter), the gate stays closed. If it’s above the level (like a snare hit), the gate opens instantly.

Once the sound passes, the gate can close quickly or slowly depending on the settings. This gives you control over whether you want the sound to stop abruptly or fade out naturally.

What an Audio Gate Does

Imagine you’re in a room with a door and someone outside playing a drum. If they hit it loud, you open the door so you can hear it. If they play softly or stop, you close the door to block the sound. That’s exactly how a noise gate works — it only lets sound through if it’s loud enough.

The basic controls on most gates are:

-

Threshold – The volume level that decides if the gate opens. Louder than the threshold? It opens. Quieter? It stays shut.

-

Attack – How fast the gate opens once the sound crosses the threshold. Fast attack is great for drums so you don’t miss the hit.

-

Hold – How long the gate stays open before starting to close.

-

Release – How quickly or slowly the gate closes after the sound drops below the threshold.

-

Range – How much the sound is reduced when the gate is closed.

Here’s a text diagram showing what happens when you set a gate for a snare drum:

The gate opens for the loud snare hit, then closes quickly, muting most of the bleed. If you set the release too short, the tail of the snare might get cut off. If it’s too long, you’ll still hear unwanted noise.

Why Gates Are Great for Drums

Drum kits are tricky to record because each microphone can hear more than just the drum it’s pointed at. For example, the mic on your snare might also pick up the hi-hat, toms, or cymbals — and all that extra noise can make the snare sound messy.

That’s where an audio gate shines. You can set the gate so it only opens when the snare is hit. This means the microphone captures the crisp crack of the snare without all the unwanted bleed when you’re not hitting it. The same trick works on tom mics to keep them clean and punchy.

Real-World Examples in the Studio

Drum Close Mics

Let’s say you have mics on the snare, toms, and kick. Without gates, the snare mic might pick up hi-hat chatter, and the tom mics might pick up cymbals or snare hits. By setting the gate to open only when the drum is struck, you keep those mics clean.

-

Example Setting for Toms:

Threshold: -20dB

Attack: 1ms

Hold: 100ms

Release: 200ms

Range: -80dB (full cut)

Overheads for 3D Sound

If you use gates on the close drum mics — like the ones on your snare and toms — you’re basically cleaning them up so they only capture the direct hit of that drum. This keeps things tight and removes a lot of the “bleed” from other parts of the kit, like cymbals or hi-hats sneaking into the snare mic.

But here’s the magic part: if you leave your overhead microphones ungated, they’ll pick up the natural ring, sustain, and decay of the drums after each hit. Overheads aren’t just there to grab cymbals — they’re also listening to the whole kit from above, including the way the sound bounces around the room. That “room tone” is what makes drums sound like they’re in a real space instead of trapped inside a box.

When you blend these two signals together, you get the best of both worlds. The close mics give you the sharp, focused “punch” — that immediate impact of a stick hitting a drum head. The overheads give you the “space” — the airy, roomy sound that lets the listener feel like they’re standing right there in the studio with the band.

A common trick among engineers is to let the overheads breathe naturally — no gates, no heavy processing at first — and then mix them slightly lower in volume than the close mics. This way, your close mics still define the attack and clarity, but the overheads sneak in just enough room sound to glue everything together. The result is clarity without losing that “you’re in the room” feeling. It’s what gives a drum recording that rich, three-dimensional quality instead of sounding flat or lifeless.

Vocals on a Live Stage

When a singer is performing live or even recording in a room with other musicians, their microphone doesn’t just pick up their voice — it’s also listening to everything else around them. That might mean guitar amps blaring nearby, the drummer’s snare cracking, the bass rumbling, or even the chatter and clinking glasses from the audience. All that extra sound can clutter up your mix and make it harder to keep the vocals clear.

This is where a noise gate on the vocal mic can be a lifesaver. By setting a gate, you make sure the microphone is only “open” when the singer’s voice is loud enough to cross the threshold you’ve set. The moment they stop singing, the gate closes, muting the mic channel and preventing unwanted sounds from sneaking through.

The benefits here are big:

-

Less feedback – On a loud stage, open vocal mics can feed sound back into the PA system, creating that awful high-pitched squeal. Gating the mic when the singer isn’t performing cuts the feedback risk dramatically.

-

Cleaner mix – The band’s sound stays tight and controlled because the vocal channel isn’t constantly picking up random stage noise.

-

More vocal focus – With less clutter, the listener hears the voice more clearly, even when the music gets loud.

For example, imagine you’re mixing a rock band in a small club. Without a gate, the vocal mic might pick up cymbal crashes every time the singer takes a breath, making the mix sound harsh. But with a properly set gate, the mic only opens when the singer delivers a line — giving you a crisp, focused vocal and a cleaner, more professional sound overall.

Electric Guitar Amps

Guitarists who play with high-gain tones — the kind you hear in hard rock, punk, and heavy metal — often deal with an annoying side effect: hum, hiss, and buzz from their amps and pedals. This noise is especially noticeable in the spaces between chords or riffs, when you’re not actually playing but your amp is still cranked and ready to roar.

The reason this happens is that high-gain setups amplify everything, not just your guitar signal. That means the electrical hum from your amp, interference from lights or electronics, and even subtle finger movements on the strings can become part of the sound whether you want them or not.

An audio gate is one of the most effective ways to keep this noise under control without killing your tone. When set correctly, the gate opens instantly as soon as you hit a note or chord, letting your powerful, saturated guitar sound come through. The moment you stop playing, the gate closes, muting the channel and silencing all that background junk.

This is especially important in fast, tight, aggressive styles where you want the music to sound precise. For example, in modern metal, riffs often have quick stops and starts. Without a gate, those pauses would be filled with hiss and feedback. With a gate, the stops are dead silent, making the playing sound cleaner and more controlled.

In the studio, engineers might use a soft gate so the noise fades naturally. On stage, a hard gate is often preferred for maximum noise suppression during those dramatic stops. Either way, the end result is the same: big, punchy guitar tone without the mess in between.

Creative Uses — “Gated Reverb” from the 80s

In the early 1980s, recording engineers stumbled onto a game-changing trick that would help define the sound of the decade: the gated reverb snare. Instead of letting a reverb trail off naturally, they figured out they could cut it short with a gate. The result was a snare that sounded enormous and dramatic, but stopped dead instead of fading away — bold, punchy, and perfect for the big, polished pop and rock productions of the time.

Here’s how it works:

-

Send the snare to a large reverb — something big and spacious, like a hall or plate reverb.

-

Insert a gate after the reverb in the signal chain.

-

Set the gate to open with the snare hit, letting the reverb burst through, but close quickly so the tail is chopped off.

The effect is powerful: each snare hit explodes into a lush, booming space, then is instantly silenced. This makes the snare feel larger than life while still staying tight and controlled — a signature sound you can hear on countless 80s hits from artists like Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel.

Troubleshooting Gate Problems

Sometimes, a noise gate can work too well — and that’s when problems start. If the attack setting is too slow, the gate won’t open fast enough, and you’ll lose the very beginning of the sound, making it feel dull or incomplete. If the release is too short, the gate will slam shut too quickly, cutting off the natural decay of the note or drum hit so it sounds choppy or unnatural. And if the threshold is set too high, softer notes or lighter hits won’t make it through at all, disappearing from the performance entirely.

The key is to use your ears and make small adjustments until the gate does its job without calling attention to itself. Most of the time, you want the listener to forget the gate is even there — unless, of course, you’re using it for a deliberate special effect like gated reverb, where the gate’s action becomes part of the sound.

Why Every Engineer Should Learn Gates

Even in today’s digital world with noise reduction plugins, gates are still one of the most effective, CPU-friendly tools for cleaning up a mix. They keep your sessions tight, your drums punchy, and your live performances clean.

And when used creatively, they can shape sounds in ways no other tool can. Whether you’re cleaning up a noisy tom track or making a snare sound like it’s in an 80s arena, audio gates are still just as relevant today as they were 50 years ago.

Buy Us a Cup of Coffee!

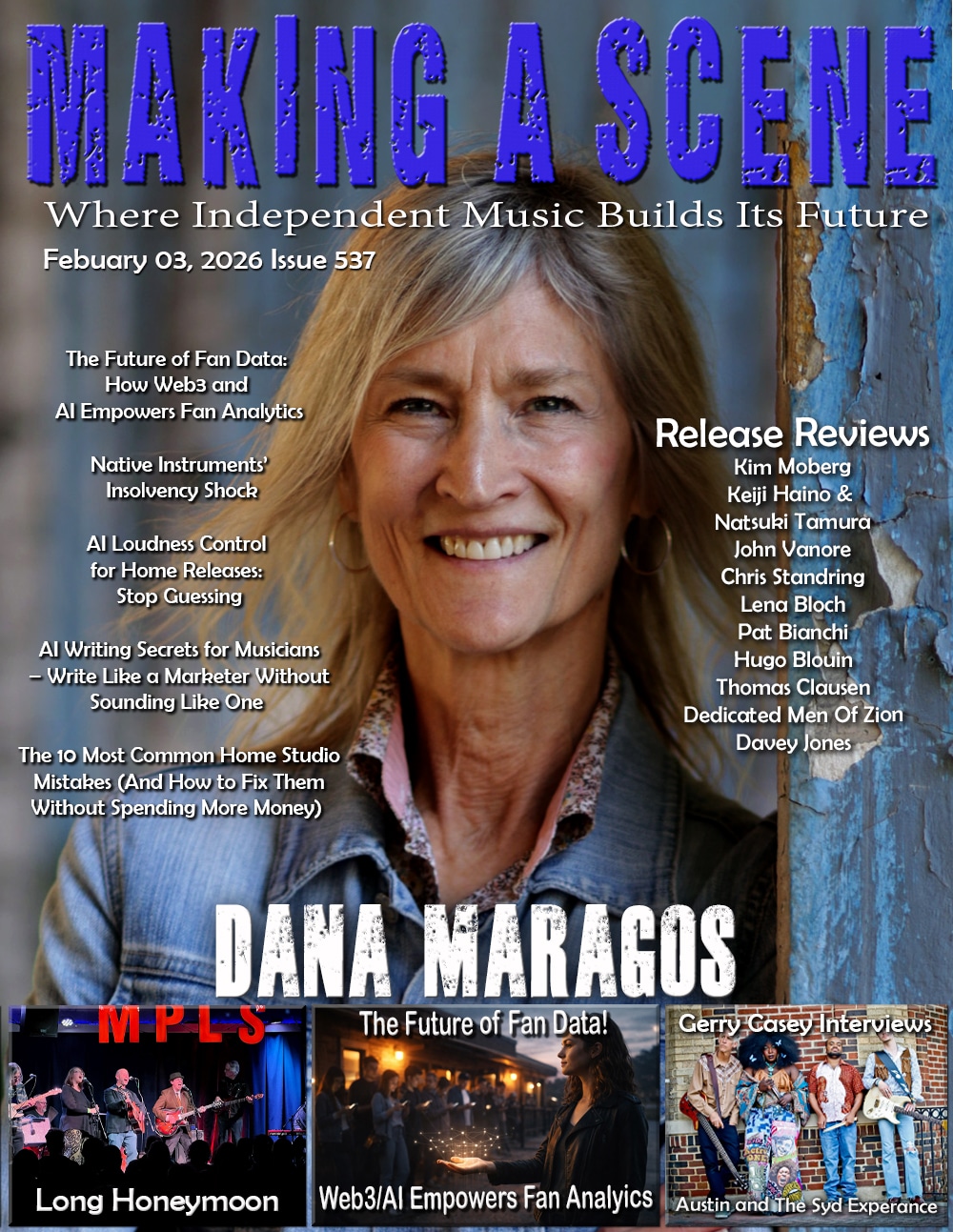

Join the movement in supporting Making a Scene, the premier independent resource for both emerging musicians and the dedicated fans who champion them.

We showcase this vibrant community that celebrates the raw talent and creative spirit driving the music industry forward. From insightful articles and in-depth interviews to exclusive content and insider tips, Making a Scene empowers artists to thrive and fans to discover their next favorite sound.

Together, let’s amplify the voices of independent musicians and forge unforgettable connections through the power of music

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Buy us a cup of Coffee!

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyYou can donate directly through Paypal!

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Order the New Book From Making a Scene

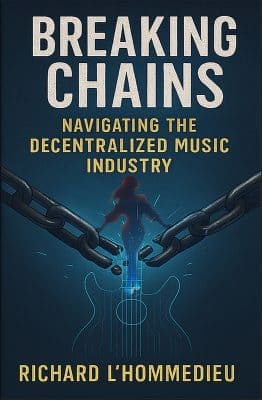

Breaking Chains – Navigating the Decentralized Music Industry

Breaking Chains is a groundbreaking guide for independent musicians ready to take control of their careers in the rapidly evolving world of decentralized music. From blockchain-powered royalties to NFTs, DAOs, and smart contracts, this book breaks down complex Web3 concepts into practical strategies that help artists earn more, connect directly with fans, and retain creative freedom. With real-world examples, platform recommendations, and step-by-step guidance, it empowers musicians to bypass traditional gatekeepers and build sustainable careers on their own terms.

More than just a tech manual, Breaking Chains explores the bigger picture—how decentralization can rebuild the music industry’s middle class, strengthen local economies, and transform fans into stakeholders in an artist’s journey. Whether you’re an emerging musician, a veteran indie artist, or a curious fan of the next music revolution, this book is your roadmap to the future of fair, transparent, and community-driven music.

Get your Limited Edition Signed and Numbered (Only 50 copies Available) Free Shipping Included

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.